*Plant Selection is the Key!

Complex historical interactions of climate, soils, pollinators, seed disseminators, and herbivory on native flora created the great forest ecosystems of the Pacific Northwest. Ecologists call our region the “Western Hemlock Zone.” The idea is that barring any type of disturbance, long-lived Western Hemlock trees will come to predominate as shade-tolerant young trees grow up to eventually replace other trees such as Douglas Fir. Open areas are usually caused by disturbances such as fire, windfall, flooding, logging, etc., but soils may play a part, too.

Sunset Western Garden Book calls our coastal climate zone in the Puget Sound Region “Marine Influence along the Northwest coast.” We have what is called a Cool Mediterranean Climate; relatively warm, wet winters and relatively cool, dry summers. People are often surprised to find out that summers in the Seattle area are usually dry. This is what helps to make Washington “the Evergreen State.” Other regions have rain in the summer. which would usually be considered the growing season. But when water is limited, plants are unable to grow. Having evergreen leaves make it possible for trees and shrubs to photosynthesize whenever temperature and moisture are suitable.

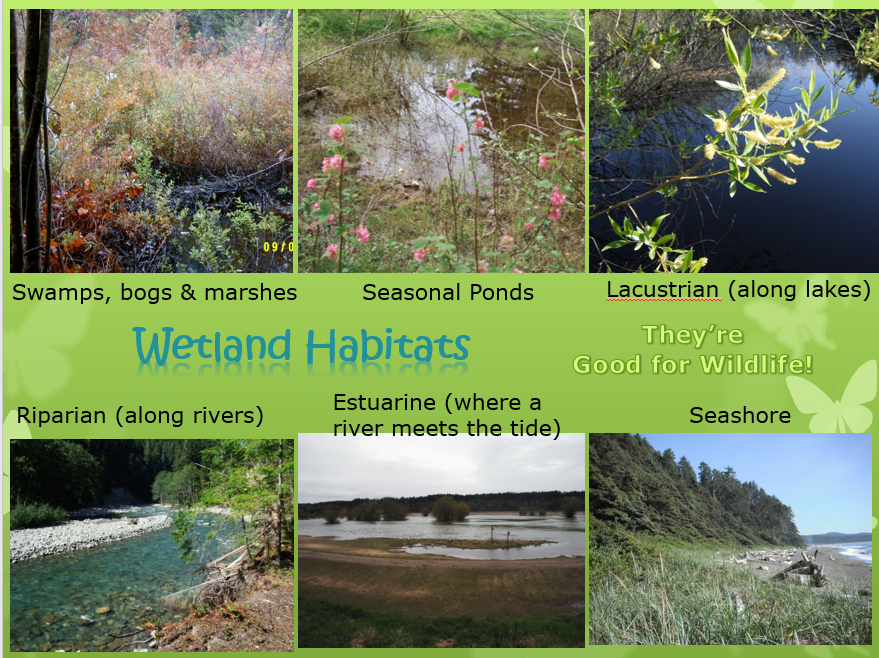

Most of our native deciduous trees and shrubs grow in moister areas near wetland habitats, which could be swamps, bogs & marshes; seasonal ponds; and lacustrine (along lakes), riparian (along rivers), estuarine (where river meets the tide), or seashore habitats. These wetland areas are especially important for wildlife. Deciduous plant species are more likely to need occasional supplemental irrigation in landscapes. As an adaptation some native plants such as Red Alders and Indian Plums may lose some leaves in late summer.

Our native soils are mostly glacial till, mixtures of clay, sand and gravel deposited by advancing & retreating glaciers. Soils in our landscapes can be very diverse depending on the history of the site regarding the accumulation of biomass, biotic (worms, microorganisms, etc.) and human activity. The physical properties of soil affect fertility, water retention and drainage. Traditional gardeners usually strive to create an ideal loamy soil. Even for a wild garden, it may be necessary to amend the soils in your landscape.

*When we are thinking about using native plants, we still need to keep in mind what is necessary or ideal for plant growth. When selecting plants for your site it is important to take into consideration the soil characteristics, how much moisture will be available to the plant, and the amount of sun or shade.

In her WSU extension bulletin, “Are Native Trees and Shrubs Better Choices for Wildlife in Home Landscapes?” Linda Chalker-Scott said her “literature review revealed that with few exceptions, the native status of trees and shrubs had no impact on wildlife biodiversity.” She argued that “wildlife will adapt to new food and habitat sources as they become available.”

It is true, that just as humans adapt to new environments, so can many species of wildlife. Some creatures, however, may have a more specialist relationship with the plants with which they co-evolved, especially pollinators adapted to collect from more specialized flowers.

By planting native species, we can also avoid the introduction of non-native species which may be wildly popular with native wildlife, such as the highly invasive, Himalayan Blackberry. Another consideration is that birds can transport non-native seeds from landscapes to distant natural habitats. We often can find non-native plants such as English Holly, Laurel and Ivy growing in forests.

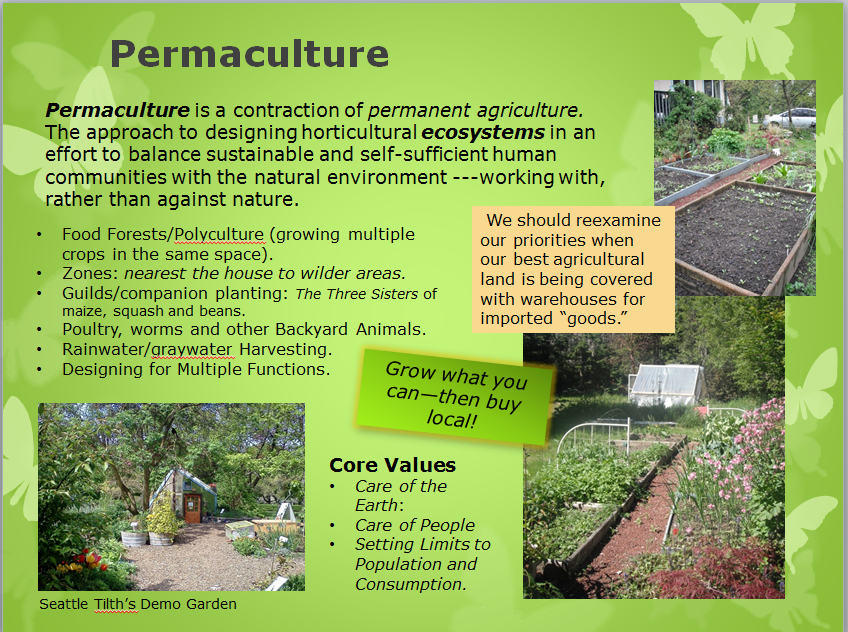

I don’t dispute the science, but I would still argue that it is better to use native species when possible. Some people are more purists and try to go 100% native, but I think 80% or so is a good goal. Also, to reduce your carbon footprint, you may want to grow some of your own food plants. Blueberries, raspberries and Asian pears are some of the easiest to grow. You can allow wildlife to share in your bounty, too!

You just need to be careful to choose appropriate plants for the intended location. If there are no appropriate natives to fulfill a certain requirement, then you can start looking for appropriate non-natives. For example, if you need a smaller tree, you might want to try a Japanese Maple. Or if you need a smaller evergreen, you may look for some cultivated conifer varieties.

Whether you want a wild natural habitat or a more formal look, it is important to do some planning to determine which plants are likely to be successful and fulfill the goals that you have.

- Plant Selection & Design: I always start out by thinking about the site in question and creating a wish list, keeping in mind how many plants I might need and the budget. I am a horticulturist, not a landscape architect, so am not very good at drawing things out. I usually just have a general idea in my head and place plants out once I get them.

- Right Plant, Right Place: As I mentioned above, selecting plants for their sun, shade, and moisture requirements is critical for success, Ultimate size needs to be considered. Large trees such as cottonwoods, conifers, alders, etc. may not be appropriate for a small yard.

- Special Goals: You may have special goals that you are trying to achieve in your landscape such as attracting wildlife (birds, butterflies, etc.), providing food, screens, erosion control, deer resistance, etc.

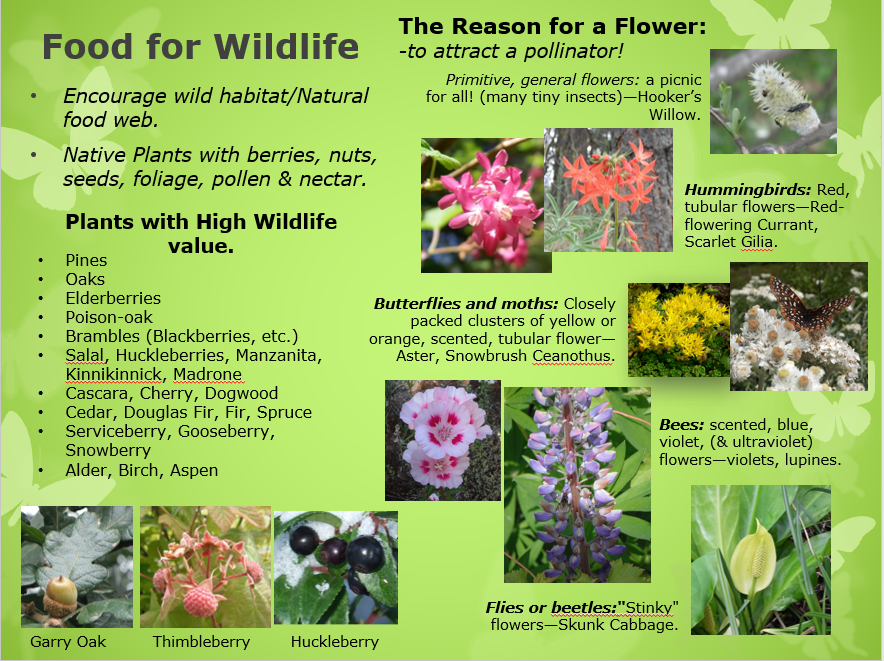

- To create a wildlife friendly habitat, you need to provide food, water, cover and places to raise young. Plants that produce showy flowers, berries and nutritious seeds, will attract pollinators, birds, mammals, other creatures and even their predators.

- Aesthetic Design Elements: We all want our landscape to be beautiful. Basic design elements to consider are focal points, scale, form, texture, color, balance, fragrance, movement.

- The 4th dimension: It is important to recognize that landscapes are dynamic, constantly changing. When planning our landscape, we want to try and visualize change through time–the seasons, years, decades, centuries…! Avoid trees or shrubs that will get too big for their location.

- Set out plants: Start with largest plants to create the “framework.” We can always add more understory plants as time and money allows. Then plant following established planting guidelines. Irrigation will be necessary, at least for the first 1-3 years.

There are many native trees and shrubs that have proven themselves as outstanding performers in home landscapes. Here are some favorites:

Alaska Yellow Cedar, Callitropsis (Chamaecyparis) nootkatensis, grows moderately slowly to 80 feet or more. It is often used in plantings close to commercial buildings; best in sun or part shade.

Mountain Hemlock, Tsuga mertensiana, is an attractive, slower-growing evergreen tree. It generally only gets 20-30 feet in gardens; best in sun or part shade.

Pacific Wax Myrtle, Morella (Myrica) californica, is our best evergreen shrub for screening. It can grow 10-30 feet tall and wide but is often kept smaller by trimming or shearing into a hedge. It fixes nitrogen in association with the bacteria, Frankia sp.; best in sun.

Vine Maple, Acer circinatum, has long been recognized as an outstanding plant for landscapes. It is a shrubby tree and can grow to 35 feet tall. Fall color ranges from orange, scarlet to yellow. It grows well in sun or shade.

Red-twig or Red-osier Dogwood, Cornus sericea (stolonifera), is usually grown for its red winter stems and attractive fall foliage. It is native throughout much of the United States and Canada. Many cultivated varieties have been developed; some dwarf varieties, some with yellow twigs, some with variegated leaves. The species generally grows 7-9 ft. spreading to 12 ft. or more. It likes moist areas and grows in sun or part shade.

Saskatoon Serviceberry, Amelanchier alnifolia, is also native across much of the U.S and Canada. It has attractive flowers and edible blue-black berries. It grows to about 20 ft. tall; best in sun or part shade.

American Cranberrybush, Viburnum opulus var. americanum; while not common in our area, this is our version of the European Cranberry Bush, which includes the Common Snowball. It has outstanding fall foliage, beautiful white lace-cap flower clusters and bright red berries. It is best in sun or part shade.

Pacific Ninebark, Physocarpus capitatus, has attractive white flower clusters, reddish dry seed capsules, and peeling brown bark. It grows to 8 ft. tall; best in sun or part shade.

Pacific Rhododendron, Rhododendron macrophyllum, is our native rhododendron. It has evergreen leaves and large pink flower trusses. It grows to 10 feet or more; best in sun or part shade.

Western Azalea, Rhododendron occidentale, is native to Oregon and California, and is very popular with gardeners. It has large fragrant flower trusses, white to pale rose, with or without a yellow blotch. It is a parent to many cultivated deciduous azalea varieties and grows 9-15 ft.; best in sun or part shade.

Indian Plum, Oemleria (Osmaronia) cerasiformis, is our harbinger of spring. Its white flower clusters and bright spring green leaves are a welcome sight after a dreary winter. It grows to about 15 ft; best in part shade or shade.

Red-flowering Currant, Ribes sanguineum, is one of our most popular natives. Its pink flower clusters attract Rufous Hummingbirds that are migrating up from Mexico in the spring. It grows to about 9 ft; best in sun or part shade.

Tall Oregon Grape, Mahonia aquifolium, has evergreen, often bronzy, holly-like compound leaves. In the spring, it has fragrant, bright yellow flowers and is attractive next to Red-flowering Currant. Its berries make a great jam! It grows 6-8 ft.; best in sun or part shade. Its smaller cousin, Low Oregon Grape, Mahonia nervosa is a good choice for shady spots.

Pacific Mock Orange, Philadelphus lewisii, has beautiful arching sprays of white fragrant flowers in spring or early summer. It grows to 9-10 ft; best in sun to part shade. It is perfect for forest edges.

Snowberry, Symphoricarpos albus, has unusual white berries and is a versatile shrub which tolerates many different conditions. It grows 6-8 ft; best in sun to part shade.

Salal, Gaultheria shallon, and Evergreen Huckleberry, Vaccinium ovatum, are two of our native evergreen staples. Both have edible berries and attractive evergreen leaves, which are used for greens in the florist trade. They both are slow to establish but can eventually get 3-6 ft. or more.

Kinnikinnick or Bearberry, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, is our best native groundcover for sun (or part shade). It has pinkish-white bell-shaped flowers and red berries. The common name Kinnikinnick is a native word for a plant that was smoked. Both scientific names mean “bear-grape or bear berry.”

Summary: When using native plants in the landscape, like with any garden plant, it is important to select plants that are likely to be successful and fulfill the goals that you have. With climate change coming upon us, we also may want to consider drought-tolerant species that are native south or east of here. Wildlife species may need to find favorable habitats if they are forced to migrate.

The new edition of Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest, 3rd Edition by Arthur R. Kruckeberg and Linda Chalker-Scott is now available. (They used 14 of my photos.) Dr. Kruckeberg sat in on many of our seminar classes when I was getting my Master’s Degree at the University of Washington. He often would say that we can’t forget about the native plants and people east of the Cascades!