Xerophytic Gardening—reducing irrigation requirements

Ever wonder why we have predominantly evergreen forests in the Pacific Northwest? Whereas, at our same latitude in the east, New Brunswick, Canada has mostly deciduous trees that exhibit brilliant colors in autumn. Most of the world thinks that it rains all the time in our region; but one of our secrets is that we have dry summers. In regions with summer rains, trees that lose their leaves in the winter, have all summer to photosynthetically replenish their energy. Evergreens, however, are adapted to be able to photosynthesize whenever conditions are favorable. Therefore in the Pacific Northwest, evergreens that have limited moisture in the summer can grow at other times of the year.

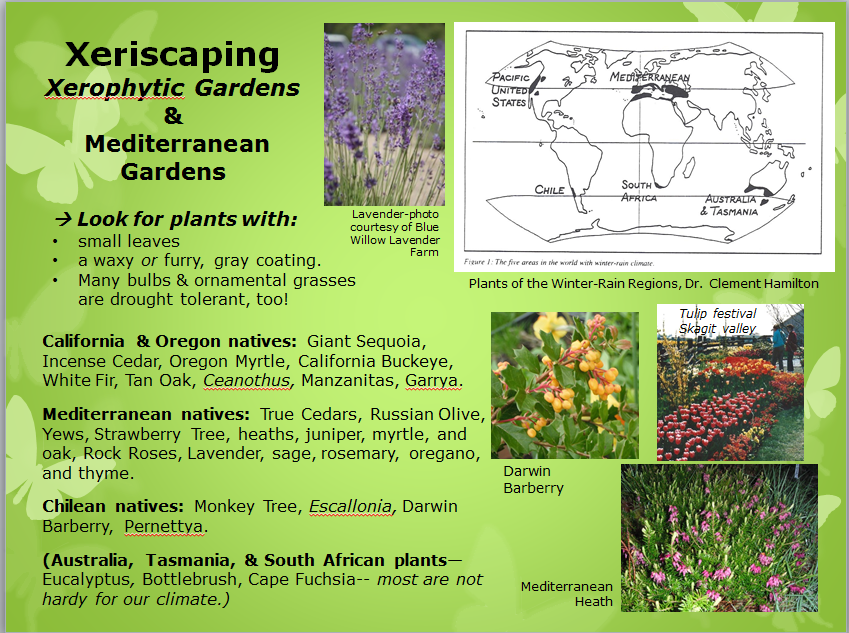

We call our mild, maritime climate, with relatively warm, wet winters and cool, dry summers, a Winter-rain or Cool Mediterranean Climate. Most other Winter-rain climates are warmer, as found in parts of Chile, South Africa, and Australia. For plants that may be better adapted to drier northwest gardens, horticulturists look for plants from these regions.

Although native plants are obviously the best adapted, plants from other winter-rain regions also do well in our drier landscapes. From Chile: Escallonias have glossy evergreen leaves and small pink flowers; Pernettyas, (Gaultheria mucronata), come in different varieties with shiny berries ranging from white, pink, red, purple to nearly black—all with a metallic sheen; Darwin Barberry (Berberis darwinii) has fountain-like growth with showy yellow flowers and blue berries favored by birds; its spiny stems make it and excellent barrier shrub. From South Africa, Cape Fuchsia, (Phygelius capensis) has loose clusters of red-orange flowers. From Australia, some of the hardier Eucalyptus trees such as the Cider Gum (E. gunnii) may be successful in certain microclimates. Several familiar landscape plants come from the Mediterranean including true Cedars (Cedrus sp.), Mediterranean Heaths (Erica x darleyensis hybrids), Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo) and the ever-popular Lavender (Lavendula sp.)

Plants adapted to withstand dry periods usually have thick, waxy leaves. Hairy leaves provide protection against drying winds. Gray or silvery foliage reflect some of the sun’s rays. Look for these characteristics when choosing “drought-tolerant” plants.

Many regions such as the Southwestern U.S. are facing severe water shortages. Some conscientious, environmentally responsible citizens that are eliminating water-guzzling lawns and replanting with natives have had to battle homeowner associations because the new look of their landscape, didn’t fit the accepted standard! Currently, in the northwest, we rarely have water restrictions—but we may find them occurring more frequently in the future.

Add compost to soil to increase water-holding capacity. Mulch to keep the soil cooler and moist longer. Reduce turf areas by planting native groundcovers or try an “eco-lawn” that requires less irrigation.

In order to irrigate efficiently, group all water-loving plants. Create focal points by planting colorful annuals in small areas or in containers. To determine how long to irrigate, measure how long it takes to fill a tuna can 1 inch deep, take an average of several places, closer and farther from the sprinkler head (different soil types may require more or less). It is better to irrigate deeply and less frequently to encourage plants to grow deep roots. Watering during the cooler, early morning hours prevents loss due to evaporation. Soaker hoses or drip irrigation systems deliver water just where it is needed. Some of the newest sophisticated irrigation systems have moisture sensors; some can even tie into the Internet and make adjustments using information from local weather reports.

Remember that any new landscape will have to be irrigated the first 1-3 seasons in order to establish good root systems!

(This article was first published in the Peninsula Gateway on Aug 5, 2009)