Ethnobotanical Garden; People, plants and plant products

People rely on plants for many things. We use them for food, building materials, medicine, clothing, dye, cosmetics, in rituals, and more. Ethnobotany is a branch of anthropology that studies the use of plants by native peoples. Unfortunately, historically, western civilization has horribly mistreated many herbalists, usually women, who used their knowledge to benefit their community. Due to their position of respect and power, they were often looked upon with suspicion by church leaders and branded as witches. Conquering armies and colonists also had little respect for the knowledge of “primitive” native peoples.

Erna Gunther’s “Ethnobotany of Western Washington” was the first and is still an often used resource on the use of plants by Pacific Northwest natives. In the 1930’s, she interviewed both women and men. Women knew the food and medicinal plants; men knew the materials in nets, fishing gear, and woodworking. Another good resource today is the University of Michigan database of Native American Ethnobotany.

The northwest could be called the “berry capital of the world,” due to the preponderance of berry bushes. Native peoples ate berries fresh, dried like raisins, cooked, mashed and dried into cakes, or preserved in fats such as oolichan grease extracted from a small fish. The most important berries for eating were Salmonberry, Salal, huckleberries, Thimbleberry, Oregon Grape, Serviceberry, elderberries, and strawberries.

Bulbs and roots were also important foods; the most important was camas. Except for Salmon, no article of food was more widely traded. Bulbs were dug in the late spring and cooked in a pit, sometimes dried after cooking and cached in baskets in trees. Undercooked camas causes severe gas & flatulence, as members of the Lewis & Clark party painfully discovered; cooking breaks down the complex sugar, inulin, to fructose. The roots of Wapato was also cooked, dried, and eaten with fish.

Western Hazelnuts were readily available if a person could beat the squirrels to them. Native people that lived near Oregon White Oaks would soak acorns to leach out the tannins or they would bury them in baskets over the winter and eat them in the spring.

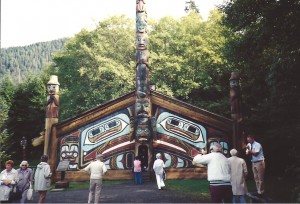

The most important tree for native people was the Western Red Cedar, also known as Giant Arborvitae or “tree of life.” The wood was used for building long houses, totem poles, canoes, cradles, etc. The bark was made into clothing, mats, diapers, etc. Limbs were twisted into rope. Baskets were made from the roots. Alaska Yellow Cedar was used similarly by natives in BC and Alaska. Douglas Fir, Western Hemlock and alder were also used for making tools and for firewood. Yew wood, prized for its strength and elasticity, was used to make tools and weapons, particularly bows. Oceanspray, known as “Ironwood” in English, was used for tools and utensils; it was made harder by heating it over a fire and polishing it with horsetail stems.

A canoe bailer & berry-picking basket from Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge’s Cathlapotle Plankhouse Interpretive Display

Many plants were used in basketry and for making mats and rope including Vine Maple, willows, Red-twig Dogwood, Trumpet Honeysuckle, Beargrass, Slough Sedge, Cattails, and Tule or Hard-stemmed Bulrush. Large leaves such as Thimbleberry, Big-leaf Maple, and Sword Ferns were used as containers or to line cooking pits or drying trays.

Cascara bark has long been known as a laxative, willow bark a pain-reliever. Yarrow and Devil’s club, a relative of Ginseng, were both used for various medicinal purposes.

It is sad when knowledge of the cultural uses of native plants is lost and not passed on to younger generations—we need to thank ethnobotanists for preserving a treasure trove of historical plant knowledge and lore.

(This article was first published in the Peninsula Gateway on June 6, 2012)