Being an environmentalist and a native plant horticulturist/botanist, I encourage the planting of native plants to help restore and preserve the natural ecology of our beautiful Pacific Northwest. However, we must also balance the needs of people with the needs of wildlife. Food is a basic need of both. That is why I often recommend planting cultivated varieties of food plants as well as native species.

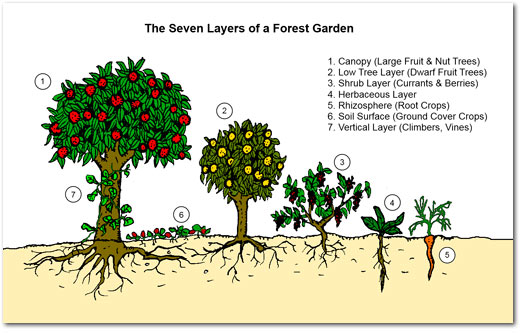

The above graphic is from permaculturenews.org.

A Food Forest, aka permaculture forest garden, is a planted garden or arboretum that mimics a woodland ecosystem but uses plants that produce edible fruits, nuts and vegetables. Fruit and nut trees are the upper level, while below are berry shrubs, and edible perennials and annuals. They are planted together instead of separating the trees into orchards and the berry bushes and vegetables into fields of single-species monocultures. Beneficial plants attract insects for natural pest management and enrich the soil by fixing nitrogen and adding mulch. “Together they create relationships to form a forest garden ecosystem able to produce high yields of food with less maintenance.” Another benefit of this type of gardening is that because of the diversity, it is not a disaster when 1 or 2 crops fail, whether because of weather, pest problems, or other reasons. The challenge, as in any garden landscape, is getting the “right plant in the right place,” with the appropriate amount of sunlight and water.

Historical hunter/gatherer societies depended on nuts, fruits, grains, and vegetables that women gathered. Their diet was supplemented by the meat that hunters brought home (once or twice a week, if they were lucky). With the advent of agriculture, people worked together to grow and preserve the food they needed.

Currently, many Americans are afflicted with diabetes, obesity and other diet-related health problems. We have an abundance of cheap, high-carb foods, with the added fat & sugar we crave along with chemical preservatives and color, flavor and texture enhancers. We are often duped by the latest diet fad or get contradictory information from doctors, nutritionists & the media. Although it is easier to buy packaged food off the grocery store shelf, eating less-processed, natural whole foods will likely be healthier for you and your family. You could even try home canning and preserving.

Nut trees and some fruit trees, however, because of their ultimate size are not well suited for backyard gardens. When I worked at Tacoma’s Wright Park, there were a couple of huge chestnut trees. Chestnuts are gathered by searching amongst the prickly husks that have fallen to the ground. It was often difficult to find nice, big nuts because people and squirrels were both competing for them. One local resident told me he would see people with flashlights searching at 1 or 2 in the morning looking for recently fallen nuts. The Black Walnut tree across the street was also popular with the squirrels. Fruit & nut harvesting could be another enjoyable recreational opportunity at local parks if appropriate tree species were planted. Hunting for and collecting natural foods can be fun for the whole family.

The Beacon Hill neighborhood in Seattle just broke ground on the “Beacon Food Forest” at Jefferson Park. A community urban farming project, it will include a traditional “Pea Patch” along with an Edible Arboretum, Nut Grove & Berry Patch. Neighborhood members will be able to harvest and preserve food for themselves and their families. I wish the Beacon Food Forest success and hope that they are able to equitably divvy up the harvest and will inspire other communities to create their own “Food Forests.”

(This article was first published in the Peninsula Gateway on November 7, 2012)