Special Habitats

Old growth forests are especially important habitats if only because very few remain due to logging and development. According to Arthur Kruckeberg in “The Natural History of Puget Sound Country,” it takes at least 175 to 250 years for a forest to begin to look like an old growth forest. It is in its prime between 350 to 750 years. Some individual trees may live to 1000 years old or more. If we make an analogy to human life spans as we do for dogs (7 “Dog-years” are said to be loosely analogous to 1 human-year). A hundred year-old forest wouldn’t even be a teenager yet!

An old growth forest actually has a greater diversity of life due to the accumulation of biomass and increased shrub & herb layer due to openings from fallen trees.

Disturbed habitats are also important because they allow different plants and animals to prosper. Hardwoods are only common on disturbed sites or special habitats such as riparian zones. Red Alder & Big-leaf Maple are the most widespread. Black Cottonwood, Oregon Ash, Big-leaf Maple, Red Alder are found on riparian & wetland areas. Pacific Madrone & Oregon White Oak are found on drier sites.

Disturbed habitats are also important because they allow different plants and animals to prosper. Hardwoods are only common on disturbed sites or special habitats such as riparian zones. Red Alder & Big-leaf Maple are the most widespread. Black Cottonwood, Oregon Ash, Big-leaf Maple, Red Alder are found on riparian & wetland areas. Pacific Madrone & Oregon White Oak are found on drier sites.

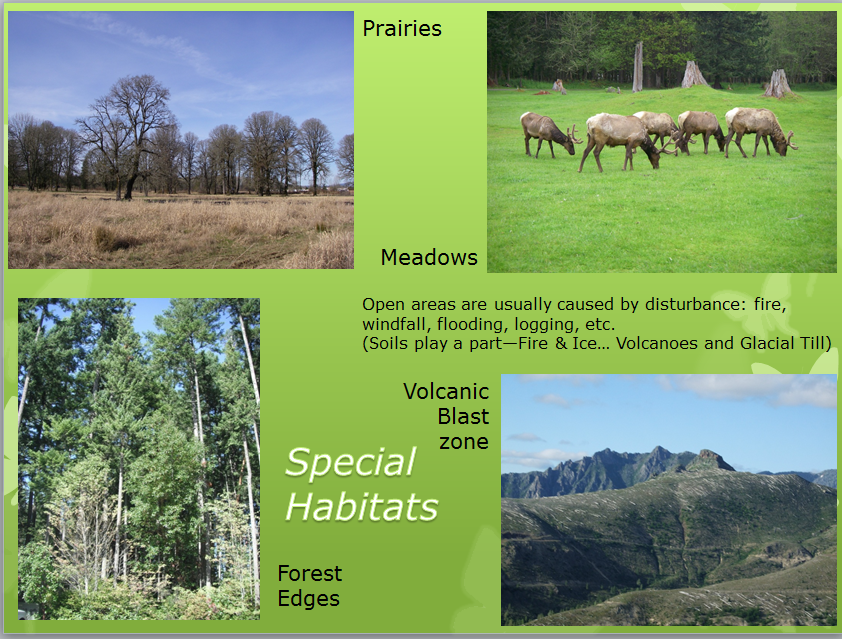

Prairies usually occur in drier areas and where the soil cannot retain much moisture or fertility. Meadows can be found in areas of frequent flooding, after forest fires, or where trees have fallen within a forest. A forest edge is an extremely valuable habitat for many wildlife species. It is an area that provides nesting sites and cover from predators. It may provide food in the form of berries, seeds, nuts or browse. Or, it may just be an area of transition for species that move between the forest and meadows.

The destructive nature of forest fire was thought to be totally detrimental for much of human history; this idea spurred the Smokey the Bear ad campaigns of the 1940’s & 50’s and the construction of lookout towers in national forests. In more recent decades, ecologists have become aware that natural forest fires are often beneficial, opening up areas that allow other organisms to move in to “restart” ecological succession. Small forest fires also reduce the “fuel load” which could cause larger, more destructive forest fires in the future. And, in fact some tree & shrub seeds need fire to be released from their cones or to break through hard seed coats before they can germinate.

We have been able to witness the recovery of ecosystems after forest fires and even after huge, widespread disasters, such as the eruption of Mount St. Helens. Life returns to recolonize, starting anew. Just as in the whole history of life on earth, the descendants of organisms that survive mold the living landscape. The interactions of each species contribute a strand to the web-of-life as each competes for earth’s precious resources.

Wetland Habitats

Water is essential to all life as we know it. All plants, animals and microorganisms need water; although how much they need and how often they need it varies between species. Wetlands are the only place that fish, tadpoles, other amphibians and many invertebrates can survive. Other species live nearby so that they can access the water or prey on the species that live there or that come to congregate at the local watering hole.

Amphibians, such as frogs, are considered an indicator species of the health of a habitat; they are very sensitive to pollution. Swamps, seasonal ponds and lakes are all important habitats for amphibians. Numerous insects and other invertebrates provide food for larger animals in all wetland habitats. Riparian habitats are important for salmon and animals that feed on salmon. Estuaries are important for many crustaceans, mollusks, and water birds.

Amphibians, such as frogs, are considered an indicator species of the health of a habitat; they are very sensitive to pollution. Swamps, seasonal ponds and lakes are all important habitats for amphibians. Numerous insects and other invertebrates provide food for larger animals in all wetland habitats. Riparian habitats are important for salmon and animals that feed on salmon. Estuaries are important for many crustaceans, mollusks, and water birds.